Teaching Through Disruption: Two Enduring Principles of Learning Design To See Educators Through Times of Change

Updated Version — Originally written during the COVID-19 pandemic, this post was updated in November 2025.

Understanding by Design — an enduring resource for lesson design.

Editor’s Note:

This post was first written in 2020, when educators everywhere were suddenly reinventing their teaching in the midst of a global pandemic. Its core themes — the challenge of questioning routines, the power of data-informed inquiry to guide practice, and the need for timeless design principles as a compass through uncertainty — remain just as relevant today. In our era of AI tools, evolving 21st-century skill demands, and rapid social and technological change, these lessons still guide the work of thoughtful teaching and learning.

When Was the Last Time Your School Questioned Daily Practices?

There’s discomfort in change, but when educators collaborate around change and it’s guided by collective deliberation and data-informed inquiry, change itself can become the focus of school-wide practices that transform learning outcomes.

In this post, we’ll look at the ubiquity of change pressures in K-12 settings, highlight the importance of embracing change, and how enduring principles of educational design can provide a stable and reliable compass for improving learning amid shifting instructional policies, challenges, methods, and innovations.

In crisis is opportunity, and so forth...

Whether the disruption comes from a pandemic, the rise of AI, or fast-changing workplace expectations, it exposes how much of education runs on habit. Routines can be a source of stability, but they can also make it hard to see where learning is—or isn’t—really happening. When disruption forces us to pause, we have an opportunity to look closer.

Questioning established practices often feels disorienting. Yet, as education researcher Seymour Sarason once argued, disorientation is a key part of the journey to professional insight. By simply asking why are we doing what we do — and testing the answers against objective evidence — they begin the process of genuine improvement. Inquiry generates some uncomfortable disruption which leads to insightful discovery.

A Lesson in Questioning: Seymour Sarason’s High School Study

In the midst of numerous shifting and failed school reform efforts, school researcher Seymour Sarason set out to put his finger on why schools often had such a hard time executing effective reforms and innovations. Based on his observations of actual educators at work in real schools, Sarason concluded that one stubborn obstacle to effective change was educators failing to critically examine the day-to-day regularities of their professional practice.

In one illustration I remember, Sarason observed a group of high school teachers who began wondering why their department — social studies — was sending home far more “fail notices” than other departments.

Stirring the pot in this way (i.e., simply stopping to ask this one question), led to two interesting discoveries…

First, teachers realized that the reason history teachers were sending out more fail notices was not because they were lazy or "bad" teachers, but because history courses were requiring students to engage in more complex open-ended analysis that students had to then process as well in extended expository writing tasks.

That was a valuable discovery for sure — one that led to discussions about scaffolding, cross-department collaboration, and better support for writing and reasoning skills.

But this was not the end of the questions...

Because it prompted someone at the school to ask the next question: Why do we send fail notices at all?

Two answers were apparent:

1) in order to get students to get back on track and master more of the content

2) because we’ve always done it this way

However, when the teachers examined the outcomes, they discovered that sending fail notifications to parents actually had no measurable effect on student performance. The same students failing midterm were still failing at semester’s end.

This finding prompted teachers to ask a question they could easily answer: "How much time do we collectively spend filling out and sending fail notices and is it an effective use of time?"

In essence, after years of simply doing what they did because everyone else did it that way for years, the teachers stopped and asked themselves: Is there any real evidence this practice improves learning?...

Of course Sarason’s story can be used to illustrate the way “routines” and what Sarason calls “regularities of everyday practice” can become self-perpetuating and largely bureaucratic or programmatic routines because of a lack of practice.

(As the famed educator Paulo Freire notes in his famous work The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, actual practice requires ongoing critical examination.)

Sarason notes that what began as a minor policy question soon snowballed into collective inquiry about instructional design, assessment, and time use.

The initial question: Is filling out and sending fail notices a good use of educators’ time? Soon led to more consequential questions:

What do social science teachers need to do to address the learning challenge in analytic thinking and writing?

What instructional changes do teachers in other departments need to implement to help with this challenge?

The teachers’ willingness to question a long-standing routine didn’t just change one school routine, it led to a chain of inquiry uncovering insights that informed the adoption of deeper instructional changes.

Of course, the most valuable lesson is that these new practices should also be examined, so what’s most important of all is fostering a sustained practice and process of collective, data-informed reflection.

Today’s “Liminal Moment” in Education

During the pandemic, schools experienced what anthropologists call a liminal phase — a threshold between the old and the new. Today, AI and automation are creating a similar in-between state. Educators again face shifting expectations, new tools, and competing frameworks for what “good teaching” means.

In this ambiguous space, it’s tempting to grasp for easy answers, or simply focus on trying out new solutions, without an adequately reflective approach and without examining underlying “regularities” of the school’s day-to-day professional culture.

— or to cling to the familiar. But lasting progress depends on holding steady to enduring principles of instructional design: clarity, coherence, and alignment. These serve as our compass when the landscape keeps changing.

There's a danger to disrupting the status quo, even a mediocre status quo, and even more than that perhaps, to disturbing a better-than-mediocre status quo…

The disruption itself, albeit in the spirit of challenging complacency, poses the risk of upsetting practices without necessarily succeeding at the next part: achieving some coherent and enduring impacts.

It is not easy to know how and when to raise questions and it can be challenging to actually make constructive improvements out of the mess you encounter as soon as you open the Pandora's box of attempting meaningful change...

Re-thinking old mindsets and practices can be refreshing, but it also can be disorienting — meaning you can simply lose your way in the end and expend energy going in circles or getting overwhelmed by complexity.

“We insult and frustrate our teachers and leaders when we keep asking them to adopt complex, confusing new initiatives and programs that can’t possibly succeed in the absence of decent curriculum, lessons, and literacy activities. These constitute the indisputable — it age-old — core of effective practice, and of education itself.”

Sometimes a grounding in the basics is a key part of advancing in skill…

Two Reliable Tools for Lesson and Curriculum Design

When the future feels uncertain, anchoring instructional design in essential frameworks help teachers stay grounded and purposeful. Two that standout are Backwards Planning and Bloom’s Taxonomy. Both work across any context — traditional, project-based, hybrid, or AI-enhanced — and ensure that teaching is structured around learning, not technology.

Backwards Planning: Designing With the End in Mind

Backwards Planning—popularized through the Understanding by Design (UbD) framework — starts with a simple but powerful shift: instead of planning from activities forward, plan from outcomes backward.

Identify Desired Results.

Begin by defining what students should know and be able to do by the end of a unit. These outcomes should align with content standards and essential competencies such as critical thinking, digital literacy, or collaboration—skills increasingly vital in the AI-driven workplace.Determine Acceptable Evidence.

Decide how students will demonstrate mastery. Will they write an analysis, present a solution, or create a digital artifact? In an era of AI-generated text, authentic assessment becomes even more important: design tasks that require judgment, creativity, or personal reflection that can’t be easily automated.Plan Learning Experiences and Instruction.

Only after identifying outcomes and evidence do you select the sequence of lessons, tasks, and tools that will guide students toward mastery. Working backward helps you stay focused on why you’re doing each activity and ensures alignment between goals and practice.

In short, Backwards Planning offers coherence amid constant change in instructional formats and tools.

It’s a key aspect of lesson design that can help ensure effective instruction and coherent learning experiences for students even as learning objectives, instructional technologies, and instructional formats change around educators or offer new opportunities to accelerate learning.

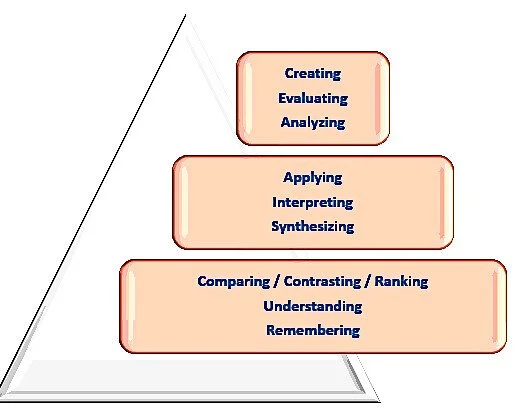

Bloom’s Taxonomy: Scaffolding Cognitive Growth

Bloom’s Taxonomy remains one of the most enduring tools in education because it describes how thinking develops—from remembering to understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating. It provides a shared language for designing and sequencing cognitive challenge.

Build upward deliberately. Rigor doesn’t mean skipping steps. Foundational tasks (recall, comprehension) give students the footing they need for higher-order tasks (analysis, synthesis, evaluation).

Cycle between levels. Learning rarely follows a perfect ladder; students move up and down the taxonomy as they consolidate understanding and transfer knowledge to new contexts.

Balance support and challenge. When AI tools can automate lower-order tasks—like summarizing or organizing—teachers can focus on designing experiences that engage judgment, perspective-taking, and creativity.

When paired with Backwards Planning, Bloom’s Taxonomy ensures that instruction builds higher level thinking skills while leading towards genuine mastery rather than fragmented “busywork.” Used together, these enduring lesson design approaches preserve intentionality and rigor, even as evolving technologies and social changes reshape how students and teachers engage in learning.

From Disruption to Design

Disruption will always be pressuring schools adapt — through new technologies, social change, or global crises. The question is how can schools do better — rather than fall prey to the pressure to simply do more or change more?

“When the number of initiatives increases, while time, resources, and emotional energy are constant, then each new initiative... will receive fewer minutes, dollars, and ounces of emotional energy than its predecessors.”

While not the whole answer, a good starting point are the principles we’ve just outlined:

Fostering a professional culture where practice is grounded in collective, data-informed inquiry

Anchoring achievement in essential learning design practices, such as Backwards Design and Bloom’s Taxonomy

Disruption can unsettle or inspire. Grounded in purposeful design and inquiry, educators can turn each new wave of change — whether AI or something yet to come — into an opportunity to reimagine teaching for deeper learning and lasting impact.

EdPro Communications hopes this inspires you to up your instructional design game.

Please share comments or questions with us!