Whether You're Talking "Remote"..."Blended"..."Project-Based"...or just tomorrow's worksheet... Start with These Two Must-Have Lesson Planning Tools

Understanding by Design is a great teacher resource for backwards planning success!

Let's face it...If you're a teacher (and you probably are if you're reading this) you know there are two kinds of "lesson plans"...

the ones that give you relief to know your students will have something "to do" in class tomorrow and will allow you to, well, make it through the day...

And then there are those other kinds of lesson plans...

You know, the kind that get video taped when a teacher is vying to earn their national master teacher certification or serving as a peer mentor to the small group of beginning teachers observing from the back row...

These lessons are part of fully mapped out sequential blocks of activities artfully incorporating a number of strands of targeted grade-level learning objectives aligned to well-defined learning goals.

At the conclusion of the unit, final assessment is integrated into a learning "product" making manifest the very holy grail of teacher craft: the integration of any number of "higher-order" thinking skills used to deepen student mastery of a set of prescribed learning objectives...whether it's more traditional learning formats (like teacher-centered direct instruction ) or more adaptive and innovative frameworks ("blended," inquiry- or project-based," "flipped classroom"...) what really makes it all tick is a disciplined approach to LESSON PLANNING—let's call it LESSON DESIGN or CURRICULUM DESIGN.

Most "curriculum designers" are not sitting in high-rise office spaces (ok, some are), but as a teacher one of your first lines of business is developing your own lesson design skills.

With everyone scrambling to adapt to "remote learning" a lot of folks are also questioning "how" and "why" they teach and design lessons in this way or on account this or that factor...

In the midst of the pivot to remote learning (all on very short notice of course), a lot of education thinkers are recommending that teachers "keep it simple"—new tools, new delivery modes—but keeping the basics the same:

video tape a lesson

provide a link to a review sheet

create one simple collaboration to incorporate "socialized learning" dynamics

wrap it up with a traditional quiz or test conducted digitally at the end of the week

repeat...

I am not arguing with the keep it simple mantra.

In times when teachers' collective sanity is at risk more than it normally is (something hard to fathom), it makes sense to cling to the familiar.

By the same token…

I also see that the very undertaking of pivoting to remote learning will inevitably lead to some questioning and collective introspection in the teaching profession—all the resurfacing of the professional introspection that usually gets deferred.

After all, teachers are too busy to question their routines when they are confronted daily with 30-kid cohorts coming through the classroom all day long at 50-minute intervals...

All the options that are coming out on the table in light of school closures, however, inevitably invite everyone back to the drawing board on some level.

Now the old routines and regularities that made daily work days more manageable are suddenly washed away.

In this liminal space the spirits of "change" and of "alternate approaches" are unleashed...

Liminal (adj.): Occupying a position at or on both sides of a boundary or threshold

Liminality (noun): Quality of ambiguity or disorientation that occurs in the middle stage of rituals

When things get stirred up this much, it is normal to "question" existing practices...

In crisis is opportunity, and so forth...

Indeed, back in the midst of numerous shifting and failed school reform efforts, school researcher Seymour Sarason set out to put his finger on why schools often had such a hard time executing effective reforms and innovations. Based on his observations of actual educators at work in real schools, Sarason concluded that one stubborn obstacle to effective change was educators failing to critically examine the day-to-day regularities of their professional practice.

In one illustration I remember, Sarason tells the story of faculty members in a high school that suddenly stopped to ask why the school’s social science teachers were sending home a lot more "fail warning" notices to parents than teachers in other departments.

Stirring the pot in this way (i.e., simply stopping to ask this one question), led to two interesting discoveries…

First, teachers realized that the reason history teachers were sending out more fail notices was not because they were lazy or "bad" teachers, but because history courses were requiring students to engage in more complex open-ended analysis that students had to then process as well in extended expository writing tasks.

That was a valuable discovery for sure—it told teachers and administrators, "We need to up our lesson design with regard to these kinds of difficult skills and higher-order thinking challenges and consider if other departments are supporting our students enough in meeting these challenges..."

But this was not the end of the questions...

The next question was: "Why do we fill out and send home these fail notices to begin with?" Of course we all know the reflexive answer is "Because we've always done it this way since we can remember..."

Of course what this question is really asking is: "How much time do we collectively spend making lists of who’s failing at midterm and then spend on filling out and sending all these notices?"

In effect, after years of simply doing what they did because everyone else did it that way for years, the teachers stopped and asked themselves: Is there any shred of evidence this practice helps facilitate learning?...

When the faculty of the school did the number crunching they discovered that the well-worn and unquestioned practice of sending out fail notices to parents actually had no benefit to student learning (because the students that were failing at midterm and got fail notices were the same students still failing at the end of the term too, in most cases).

Of course Sarason is using this story to illustrate the work habits of teachers in schools everywhere.

He wants to remind his readers that when teachers hold fast to routines as defenses against the intense social interactions of their daily work and the intense time pressures of their work day, then merely stopping to engage in the natural act of questioning those routines will inevitably lead to some disorientation. Then, one question inevitably leads to another, highlighting why there’s resistance to raising questions in the first place. In the case of the teachers Sarason was observing, the string of questions went far beyond a mechanical policy question about whether to keep writing the fail notices or not. It led to insights that would inform real changes in core instructional practices. The initial questions seemed insignificant, but the mere act of questioning led to deeper insights in the end.

First these teachers asked…

Is this really a good use of time?

What skills do students really need?

What evidence do we have that a given practice is really helping students master the critical skills and knowledge they are lacking?

What do social science teachers need to do to address the learning challenge in analytic thinking and writing?

What instructional changes do teachers in other departments need to implement to help with this challenge?

Turning so many factors upside down, the pandemic has obviously broken the trance of day-to-day regularities (to use Sarason's term) and opened the door to re-thinking, which opens doors to a disorienting other-world populated with frameworks and options vying for our attention—because, as we know, the world of pedagogy is rife with competing theories and pedagogies…

It is not easy to know how and when to raise questions and it can be challenging to actually make constructive improvements out of the mess you encounter as soon as you open the Pandora's box of attempting meaningful change...

There's a danger to disrupting the status quo, even a mediocre status quo, and even more than that perhaps, to disturbing a better-than-mediocre status quo…

The disruption itself, albeit in the spirit of challenging complacency, now has an even greater risk of upsetting practices without necessarily succeeding at the next part: achieving some coherent and enduring improvements to professional practices at one's school...

All these challenges are reasons why "keep it simple" is often a good motto, but it's also playing it safe, and innovation (change) requires some risk taking...

As the mystics can be counted on to remind us, in times of disorientation it is natural to grasp for a compass, for a way forward that is "centering"—that is essential and reliable...

Re-thinking old mindsets and practices (in this case because educators must close physical classrooms and figure out remote learning options) can be refreshing, but it also can be disorienting—meaning you can simply lose your way in the end and expend energy going in circles or getting overwhelmed by complexity.

Sometimes getting back to basics is a key part of advancing in skill…

However it is that you as a teacher might be going about the business of trying to survive this time of questioning, seeking perhaps to engage in using it as an opportunity to put into practice new lesson design insights, I always found that effective lesson design, whatever framework or construct you're working in or told by the district office to adopt will be easier to master with the help of these two (once trendy, now old-school) constructs:

1) Backwards Planning (for help sequencing and coordinating instruction around well-defined learning objectives)

2) Bloom's Taxonomy (for selecting and designing appropriate tasks and activities for each stage of learning)

Whether starting a new unit design from scratch or pivoting to a new mode of instruction (say remote learning or project learning), BACKWARDS PLANNING and BLOOM'S TAXONOMY (or an equivalent schema) are two mental templates you can rely on to up your lesson planning results in all scenarios.

Did you get recommendations on using these two design templates in your teacher certification courses?

I think most teachers do...

If you did, do you really use them in the haze of day-to-day work and deadlines?…

Here are the nuts and bolts of effective lesson design when you anchor it with these two tools:

1) Backwards Planning—

…starting with a well-defined end point

Define what you want your students TO KNOW and BE ABLE TO DO by the end of the unit of instruction (guided by Common Core in conjunction with other identifiable frameworks adopted at your school, e.g., 21st Century Skills; Teaching Tolerance; Digital Citizenship...).

In other words, you start by creatively envisioning what kind of learning product and summative unit assessment will engage students and also challenge them to demonstrate mastery of the key learning objectives (skills, concepts, knowledge...). Or, you define at least key parameters for this summative assessment or project but leave some flexible options around final design (e.g., allowing student voice/choice in the assessment format…allowing space for pragmatic adjustments supporting the end goal as the unit unfolds...).

Next, working backwards, identify a sequential list of skills, knowledge, and concepts students will need to acquire in order to develop mastery of the summative learning objectives you defined...

Planning BACKWARDS from this sketch of what "student mastery of the learning objectives" will look like in terms of concrete student tasks at the end of the unit, you can ask yourself if you are setting "high expectations for all learners" and then map out what skills, ability, and knowledge students need along the way in order to succeed at the end of the unit.

As you work backwards from this end point (i.e., what students need to know and to be able do by the end of the unit), you plug into your lesson calendar sub-units of instruction clustered around sub-skills and sub-concepts student need to acquire.

For each of these instructional modules, you can ask yourself:

what skills/knowledge will students need to master in this module?

what existing or prior knowledge/skills are they starting with?

By the end of this process you should have a sort of sequential itinerary of knowledge and skill destinations, each one a direct building block for a subsequent knowledge or skill destination on the unit itinerary.

For each day and week of instruction you now have a template to guide you in a way that logically and effectively does what good teaching does (in any pedagogical framework or setting): it facilitates student learning sequentially for mastery of a prescribed set of well-defined learning outcomes.

2) Bloom's Taxonomy—

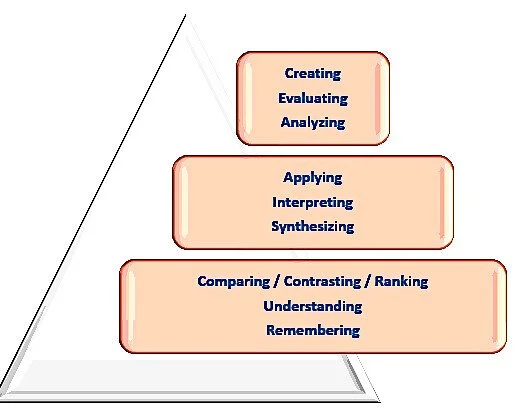

Bloom's Taxonomy helps teachers measure the depth of thinking and complexity being targeted by their lesson activities and helps them think about planning instructional units, and modules within larger units, with proper "scaffolding"—using the taxonomy as a check list of sorts to help ensure they are not skipping over skill steps or merely being content to make lesson activities that fail to target higher-order thinking.

In other words, Bloom's Taxonomy is a reminder to include higher-order thinking tasks but also a reminder that effective teaching is not just about adding "rigor" to your students' assignments, it's about when to incorporate lower-order thinking tasks for scaffolding--for the purpose of facilitating student learning by ensuring they have incremental opportunities to acquire the knowledge and skills they need to accomplish more rigorous academic tasks later in the module and as they progress through the longer instructional unit.

As a teacher, you probably get this concept…If not, think of it this way:

you can't ask a student to write an engaging paragraph, and by extension build an engaging essay from a string of paragraphs, if you haven't first ensured they understand what a paragraph is, see it used contextually, engage with effective and ineffective models (compare, contrast, rank) and develop some understanding of the conventions and practical aspects that make sense of "paragraphs" (their origins, utility, relation to writing and communication...).

If you are going to ask your students later in the unit to construct something using complex analysis and organizing skills and require them to communicate this in some developed expository format, then this lower-order instructional activity (presenting students the definition of "paragraph" and so on) is part of building depth of knowledge that will support higher-order tasks.

Thinking Skills Pyramid (based on Bloom’s Taxonomy)

(EdPro Communications 2020)

Now, sometimes teachers get the message that "lower-order" is bad teaching because it's dull and lacks rigor (e.g., teaching a list of vocabulary words), while activities that require higher-order tasks represent good teaching because these tasks are increasingly engaging and rigorous as you go up the pyramid. Highest order thinking involves “deeper” learning, analysis and synthesis—such as students marshaling complex evidence and arguments.

However, all levels on the hierarchy represent operations students will need to develop and put to work over and over in a range of endeavors and for success at the next level of learning.

AND…

in terms of instructional strategies you, the teacher, will want to cycle over and over again between lower-order tasks and higher-order tasks, based on the immediate learning goals, student needs, and instructional priorities guiding discrete activities within any module of instruction across a larger unit of instruction.

In authentic and effective lesson design, different types of tasks (in terms of where they fall on Bloom's Taxonomy) have their proper place, a place suited to the logic of the learning sequence and for supporting students with different aptitudes and prior knowledge as the teacher helps facilitate students' growing ability to acquire and demonstrate mastery.

Giving students dull, rote tasks just to provide an "activity" and keep them busy is not an optimal lesson design approach…

However, putting high-expectation,-higher-order-thinking-tasks before students can be equally problematic…

Focusing on higher-level tasks without the right pyramid structure in place, there is the risk of simply setting many of your students up for failure.

Combining BACKWARDS PLANNING and BLOOM’S TAXONOMY the goal is to robustly support incremental learning so that all students have opportunities to succeed or at least grow in some rewarding measure when asked to attempt the more rigorous tasks.

Too many to mention perhaps are all the collateral benefits and professional rewards that flow from this kind of coordinated lesson design...but they include:

helping students track their own progress

helping students see learning in terms of acquired skills and practice (developing a learning mindset as opposed to a succeed-vs.-fail mindset)

ensuring day-in and day-out that your instruction is essentially (albeit not perfectly of course) aligned with a clearly defined, rigorous, and engaging learning outcome and learning endeavor

having a ready answer for the student who says, on any given day, or in the context of any given activity "Teacher, why are we doing this??"

having a way of explaining grades and evaluation marks in highly objective terms anchored in quick and fast assessments of students' (evolving) mastery of TARGETED concepts and skills within manageable but linked and synergistic blocks of instructional focus and learning acquisition

So in this time of educator disorientation it's a good time to get back to basics in order go beyond the basics when it comes to lesson planning, with help from these two useful frameworks: BACKWARDS PLANNING and BLOOM'S TAXONOMY...This way you don't have to choose between "keeping it simple" or else "losing your way."

EdPro Communications hopes this inspires you to up your instructional design game.

Please share comments or questions with us!